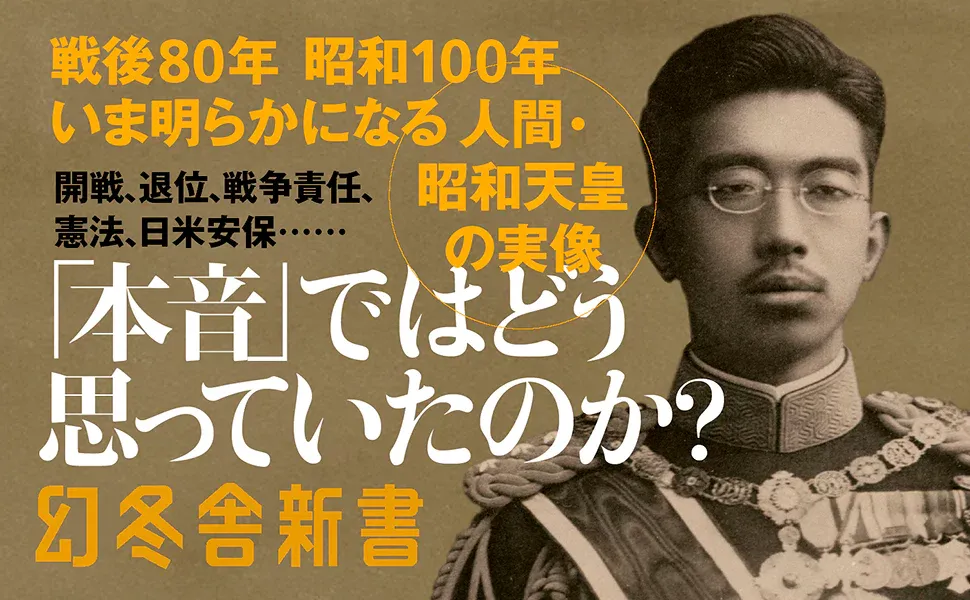

Emperor Hirohito repeatedly advocated for the necessity of rearmament -- an interview with journalist Ryuichi Kitano

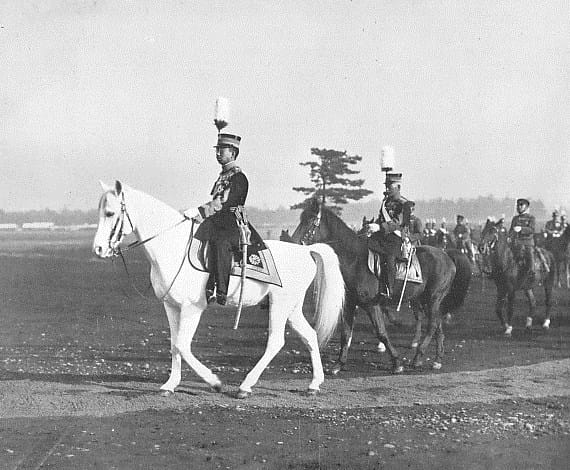

The Showa Emperor was a deeply divisive figure whose role in the tumultuous period from 1933-1945 was clouded by lingering postwar taboos and censorship. Since his death in 1989 multiple accounts have given us a clearer picture of his thoughts and actions in ways that are often unflattering.

Ryuichi Kitano, long-term staff writer for The Asahi Shimbun, has published a new book on Emperor Hirohito: The Showa Emperor as Seen by His Close Aides: Tracing Showa History Through the Emperor's Words and Deeds (『側近が見た昭和天皇 天皇の言動でたどる昭和史』)

How does your book incorporate the most up-to-date scholarship by historians on the Showa Emperor?

Over the past decade, several key historical accounts have been released. These include the The Diary of Saburō Hyakutake (百武三郎日記), Grand Chamberlain from 1936 to 1944 during the prewar and wartime periods; and the The Show Emperor’s Private Journal (昭和天皇拝謁記) by Michiji Tajima, who was director-general of the Imperial Household Agency from 1948 to 1953.

These are diaries and records kept by close aides who served Emperor Showa before and during the war years. They represent firsthand accounts, written in real time, of the emperor's private words spoken only to his inner circle, making them primary historical materials of the highest order. They give us a picture of the emperor as a human being.

Is it fair to say that we now have a complete historical picture of his life and the decisions he made?

Professor Akira Yamada of Meiji University, an expert on modern Japanese and military history, notes that the official record “consistently emphasizes the narrative of a peace-loving emperor who avoided war, seemingly glossing over anything that contradicts that image.” It is known from the diaries of prewar and wartime chamberlains and military officers that Emperor Showa was deeply involved in the decision to go to war against the United States and provided detailed guidance on the conduct of the war even after hostilities began. These points, however, have been carefully omitted from the “Showa Emperor's Official Record.”

The Showa Emperor's Official Record (昭和天皇実録)were compiled by the Imperial Household Agency and published in 2014. The set comprises 61 volumes: 60 volumes of main text and one volume containing the table of contents and explanatory notes. Approximately 3,000 historical documents were used in the compilation, including about 40 previously unknown materials. Numerous previously unrecorded anecdotes, including those from the emperor's childhood, which had been poorly documented, were revealed for the first time. On the other hand, direct quotations of the emperor are extremely rare: Most entries are just summaries of his statements.

The Imperial Household Agency adopted a policy of recording only content based on reliable sources. Consequently, even previously known information not covered in the Showa Emperor's Official Record is frequently omitted. These omissions include statements reportedly expressing displeasure over the enshrinement of Class-A war criminals at Yasukuni Shrine and the Emperor's eleven meetings with General Douglas MacArthur, supreme commander of the Allied Powers (GHQ).

One of the key issues of the wartime emperor is how much responsibility he had for starting and prolonging the war. Was he a dynamic wartime leader, or merely a pawn of the military and political class? Has that debate finally been resolved?

The conclusion I have reached is that the emperor was not merely a pawn of the military and politicians. As for whether he was an active wartime leader, I believe there were periods when he was, and periods when he was not. Nonfiction writer Masayasu Hosaka, an expert on Showa history, has spoken about the emperor’s views on war. I fully agree with his perspective, so I quote it below:

I believe the emperor was neither a warmonger nor a pacifist; his fundamental stance was the preservation of the Imperial line. He would prefer not to fight if possible, but would wage war if necessary for the Imperial throne, and would choose peace if peace better safeguarded the throne. The process leading to the 1941 declaration of war against the United States shows the emperor initially being passive, thinking ‘I dislike war,’ yet gradually accepting it. This shift likely occurred because military leaders persistently persuaded him, arguing ‘If we do not fight, the nation cannot survive, and the Imperial throne cannot be protected.’ It becomes clear that, while he didn’t like to, he found himself in a position where he had no choice but to decide on war.

Were you surprised by anything in the research? Do ordinary Japanese still have misunderstandings about the Showa Emperor?

Some of the emperor’s more candid remarks are cited in The Showa Emperor’s Private Journal (昭和天皇拝謁記) by Michiji Tajima, who was grand steward of the Imperial Household Agency from 1948 to 1953. Some surprised even me. Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, enacted in 1947, renounced war and prohibited the maintenance of military forces. The emperor never publicly expressed his views on this in official settings. However, these memoirs revealed for the first time that he frequently voiced dissatisfaction with the provisions of Article 9 to aides like Tajima and repeatedly advocated for the necessity of rearmament through constitutional revision.

According to Tajima’s account, the emperor was not necessarily positive about postwar democracy and lamented that students participating in political movements, such as the 1960 student protests against the revision of the Japan-U.S. The Security Treaty was a “troublesome matter.” Analysis of handwritten drafts of waka poems believed to have been written by the emperor shortly before his death reveals for the first time that he sympathized with former Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi. Kishi had faced strong student opposition while attempting to advance the treaty revision and resigned after the Diet ratified the treaty.

Has the debate whether the Showa Emperor was a dynamic wartime leader or merely a pawn of the military and political class finally been resolved?

First, I believe the vast majority of Japanese people have little knowledge or interest in the emperor. Even those with some knowledge or interest in the Imperial Family are not particularly well-informed about his actions and statements before and after the war, and many seem to simply believe the image of the “emperor who loved peace” disseminated by the government. However, a significant minority of Japanese do believe the emperor should bear responsibility for the war. This view is particularly common among left-leaning liberals who believe Japan should accept responsibility for its aggression against Asian nations.

Immediately after defeat, the view that the emperor should abdicate to take responsibility for the war held sway not only among leftists but also among government officials and former military officers – the leadership that had guided Japan before and during the war. Although the pre-war Constitution of the Empire of Japan granted the emperor immunity from legal and political accountability, the call for him to take moral responsibility remained strong.

According to the Tajima papers, the emperor himself stated, “For me, leaving my position would be an easy way to take responsibility. It is precisely because I feel this moral responsibility that I must make the painful effort to rebuild.” He expressed that remaining in his position was how he would fulfill his responsibility. In contrast, Tajima, who before becoming head of the Imperial Household Agency believed the emperor should abdicate to take responsibility, responded to the emperor's statement by saying, “Given that not a single person in a position of authority before or during the war remains today, while His Majesty alone continues to reign, I think the abdication argument arises.” He thus frankly conveyed that the emperor's argument that “it is precisely because I feel responsibility that I remain on the throne” would likely be difficult for the public to understand.

The popular right-wing party Sanseito, for example, recently urged “respect for the Imperial Rescript on Education” issued in 1890 by Emperor Meiji, outlined the virtues that the “subjects” of the Japanese Empire were expected to uphold. How important is the emperor to contemporary Japan?

In modern Japan, the emperor's presence is scarcely noticed. We’re only reminded of his existence through news coverage of disaster relief visits or memorial services for war dead, or perhaps when people gaze with admiration at his splendid ceremonial attire during formal occasions.

Of course, for right-wing groups emphasizing Japanese identity, the emperor is a figure of immense importance. This explains why right-wing parties, including Nippon Ishin no Kai (Japan Innovation Party), emphasize the Imperial Rescript on Education and visits to Yasukuni Shrine.

However, the right wing believe the Imperial Household should conform to their idealized image of the emperor, irrespective of the facts. The most prominent example of this is the debate surrounding Imperial succession. Within the Imperial Family, Prince Hisahito of the Akishino family (the emperor’s younger brother who is second in line to the throne) is the only male heir born in the past 40 years. The right clings to the notion that succession through male-line descendants is Japanese tradition, strongly rejecting female emperors or succession through the female line.

In stark contrast to European monarchies that have recognized female succession, Japan still permits only succession through male-line descendants. This stems from the right’s fixation on the idea that the living emperor and his family should conform to their idealized vision. They have rejected perspectives such as respecting the emperor and the Imperial Family as human beings in their actual state, or the need to reconsider the male-line succession system to prevent the imperial bloodline from terminating.

While Japanese public opinion polls show over 70% support for allowing female or matrilineal emperors, the voices of the roughly 30% of right-wingers who firmly oppose this are louder. Furthermore, the right holds significant influence among politicians, including Diet members. Consequently, despite discussions on female or matrilineal emperors beginning 20 years ago in 2005, it has not happened. In the debate surrounding imperial succession, it seems the strong minority holds more influence than the weaker majority.

Comments ()